Week 3: Brand Architecture

Brand architecture is the structure on which the brand is built. It’s the way an organization interacts with its brands and how they interact with each other. This strategy may take many forms, but can usually be distilled into two categories: a “branded house” or a “house of brands” (Keller, Apéria, & Georgson 2008). A classic example of the branded house is FedEx, where each service is just visually branded with a different color.

You always know it’s FedEx.

A major example of a branded house is Unilever. This Dutch giant’s products are not marketed on the parent companies name. Each brand is positioned on its own, and they do very little to reflect upon each other.

Just a few of Unilever’s brands.

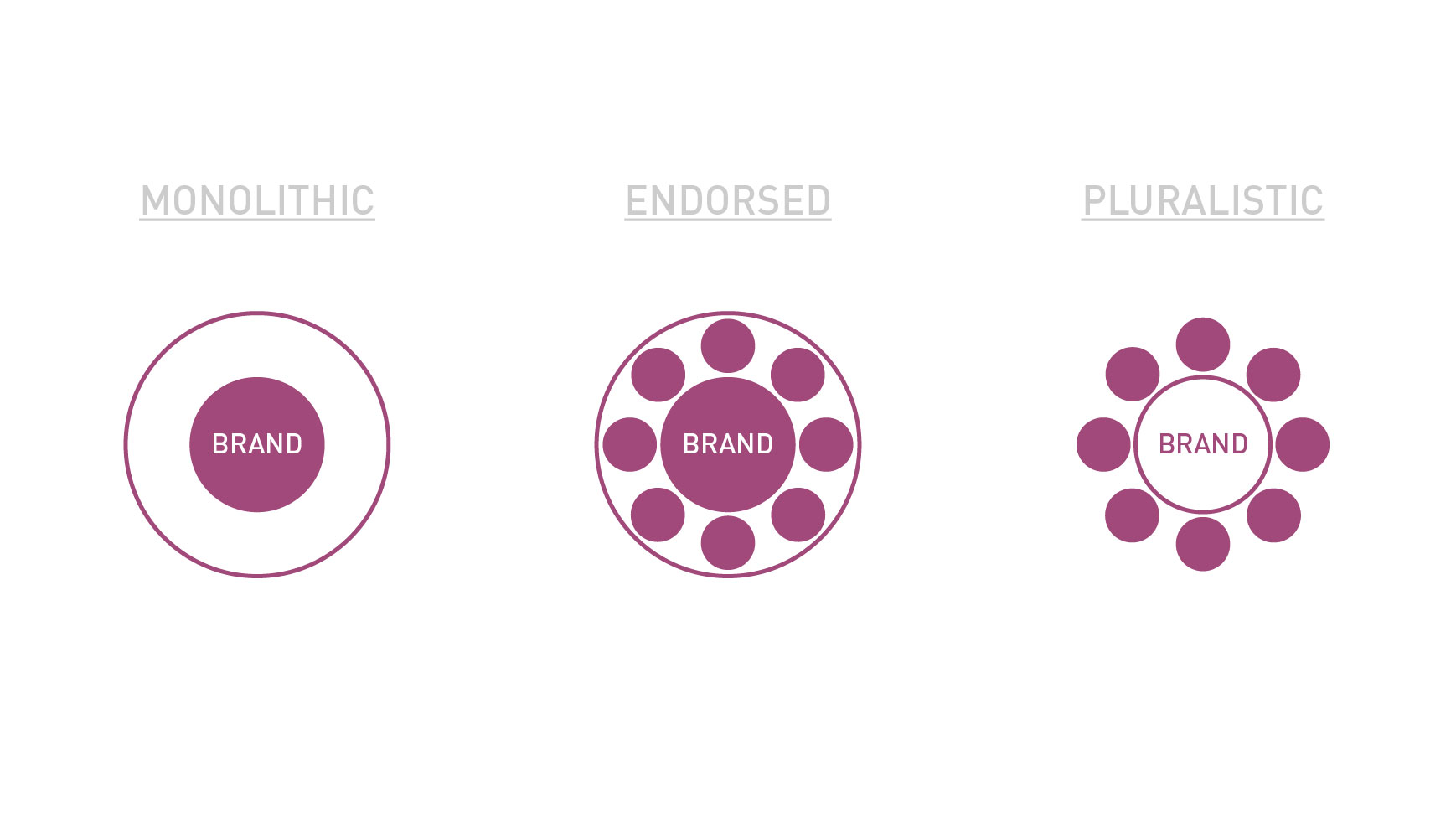

Another way to describe brand architecture is to define whether its structure is monolithic, endorsed or pluralistic (Lischer 2017).

We'll be using both methods as we look at a few companies below.

Example 1: Volvo

Volvo’s brand architecture is based on is largely based on the parent brand alone. This form is known as a “branded house” or a “monolithic brand”. Every vehicle produced by the Swedish carmaker is sold as a Volvo with the product identified by an alphanumeric product code. This allows Volvo to make sweeping statements that are all encompassing to every brand or product in their portfolio. Once upon a time, that statement was Volvo equals safety. Lately, that messaging has been somewhat muddled by a push for luxury and performance. This is one of the issues with the branded-house model. Marketing missteps affect every product in the portfolio. Volvo does have a trucking division that operates many different brands, but for the sake of simplicity, we’ll ignore that part of the portfolio.

Brand strategy:

Example 2: Carlsberg

Carlsberg functions as a hybrid of a house of brands and a branded house or an endorsed/pluralistic brand. The master brand contains several products bearing the Carlsberg name and logo. The Danish brewer also has hundreds of other beverages under various brands, with a wide range of positioning strategies. Many customers are completely unaware they are drinking a Carlsberg product.

Brand strategy:

Example 3: Apple

Apple’s brand architecture is based on an endorsed brand structure or could be viewed as a hybrid approach. Every product is undoubtedly Apple but may occupy its own brand space (e.g. the iPad vs the MacBook). The most valuable company in the world prides itself on its holistic ecosystem of products while letting each product have an identity of its very own.

Brand strategy:

Pro’s and Con’s of each strategy

Pro’s

|

Con’s

|

No worries of cannibalization

|

Everything is reflected back onto the brand and all of its products

|

Much simpler to manage

|

Nothing to fall back on

|

May inspire deeper brand loyalty

|

May not be able to transition or pivot successfully.

|

Pro’s

|

Con’s

|

Brands allowed to stand on their own

|

Everything is reflected onto the parent brand

|

Support from the parent company

|

One individual brand may taint other family brands

|

Cross-selling may be easier

|

Each brand requires its own marketing and other various costs

|

Pro’s

|

Con’s

|

A brand can support the company through crisis.

|

Extremely difficult and expensive to manage.

|

Brands do not have to conform to others in portfolio

|

Parent company does not get credit for successes in the public eye.

|

Can appeal to drastically different segments

|

Different strategies, management, marketing etc.

|

What does this mean for organizations?

While all structures can theoretically work for almost all industries, some are better than others in certain fields. Organizations such as Unilever are built off of acquisitions and house drastically different products in their portfolio. For them, it makes the most sense to utilize the pluralistic philosophy and let each brand stand on its own without the burden of trying each one back to a common standard. For tech companies and car companies, it's often logical to use the endorsed brand framework. Chevrolet wants its customers to know that it stands by several guiding principles while also projecting a different feeling with each individual brand (Think Corvette vs. the Volt). Monolithic brands are typically small startups or are specialized in just one field or have built a name that is synonymous with excellence (see the FedEx example above.

How do companies with a pluralistic brand structure keep it all straight?

Large organizations with large brand portfolios face many challenges when it comes to understanding how their individual brands interact with each other in the marketplace. One tool to address this problem is the Brand-Product matrix (below).

The brand-product matrix as seen in Strategic Brand Management (Keller, Apéria, & Georgson 2008).

In the matrix shown above, The rows are for brands and/or line extensions and the columns are for individual products. This can map out where brands overlap each other in a simple format, allowing the umbrella organization to further understand how each brand interacts with one another in the marketplace. To help explain this model, let's take a look at a couple of skincare brands from Johnson & Johnson.

While this is just a small sample of the gigantic range of products Johnson & Johnson produces, it is demonstrative of how this matrix can be implemented. Each brand has its own identity and positioning. Neutrogena is their all-encompassing skin care and cosmetic brand; whereas Aveeno is their natural, sensitive skin brand; and Clean and Clear is their problem-skin care solutions brand. Even with these distinctions, we find plenty of overlap. Once the matrix is filled in, the parent company can analyze sales and positioning of each product and determine whether to reposition, cancel, rebrand, or allow them to remain.

For a much more concise explanation of brand architecture check out the DocStoc video below:

Sources:

Deole, A. (2016). Types of Brand Architecture – Yellow Fishes – Medium. [online] Available at: https://medium.com/@theyellowfishes/types-of-brand-architecture-4fb85866bd1d [Accessed 10 Sep. 2018].

Docstoc. (2011). Brand architecture: Phases of Strategic Brand Development. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wZH9sz4nenI [Accessed 10 Sep. 2018].

Keller, K., Apéria, T. and Georgson, M. (2008). Strategic brand management. Harlow: Pearson, pp.503-505.

Lischer, B. (2017). Brand Architecture: Creating Clarity From Chaos. [online] Ignyte. Available at: http://www.ignytebrands.com/brand-architecture-creating-clarity-from-chaos/ [Accessed 10 Sep. 2018].

Lischer, B. (2017). Brand Architecture: Creating Clarity From Chaos. [online] Ignyte. Available at: http://www.ignytebrands.com/brand-architecture-creating-clarity-from-chaos/ [Accessed 10 Sep. 2018].

Hi, I find reading this article a joy. It is extremely helpful and interesting and very much looking forward to reading more of your work.. naming a business

ReplyDeleteMarketing management orientations are different marketing concepts that focus on various techniques to create marketing management orientation, produce and market products to customers. The management usually focuses on designing strategies that will build profitable relationships with target consumers.

ReplyDeleteBrand creation is a dynamic process that evolves with the changing needs and preferences of consumers. Teaching high school students about brand creation in their marketing textbooks would prepare them to navigate the ever-changing landscape of branding.

ReplyDeleteThis is an insightful post on brand architecture! A well-structured brand identity is essential for businesses across all industries, including furniture brands. High-quality visuals play a significant role in shaping consumer perception and enhancing brand appeal. Professionally edited images ensure that furniture pieces look flawless, well-lit, and visually appealing. A professional furniture photo retouching service can enhance colors, remove imperfections, and refine textures to make product images stand out. Strong visuals help build customer trust and improve sales. Thanks for sharing these valuable insights—looking forward to more branding discussions!

ReplyDeleteBrand architecture defines the structure of a hostbet company’s brand portfolio, organizing brands into a clear hierarchy. It helps in ensuring consistency and clarity in messaging for each target audience.

ReplyDelete